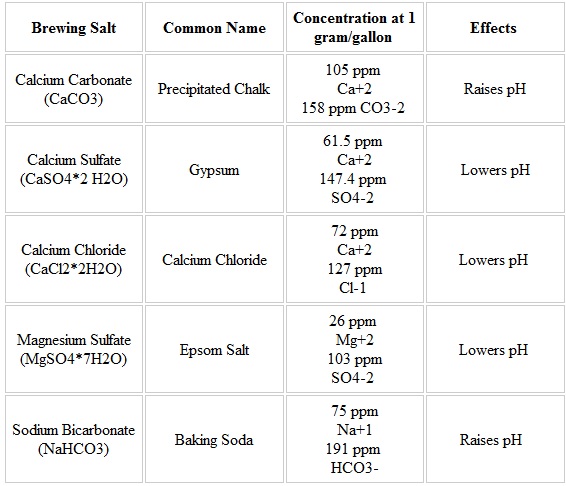

Known for its signature hop snap, Stone Brewing in San Diego keeps the bitterness in its west coast takes on New England IPAs. (Note: brewers usually use calcium sulfate – gypsum – and calcium chloride salts to adjust their levels.) West Coast IPA Water Profiles “For snappier west coast style IPA’s we increase the calcium sulfate,” she says. Veronica Vega, director of product development for Oregon’s Deschutes Brewery, aims for around 200ppm of chloride in her hazies. “I loved how the higher calcium chloride additions and chloride:sulfate ratio could lend a pillowy softness and subtle sweetness to the beer, which could help improve high attenuation scenarios and also accentuate the juicy qualities of the style,” he writes. Whereas much of the literature on the topic uses 150-200ppm as a general target (the same range Wambles uses for his stouts), he’s gone as high as 300ppm. He says chloride can and should be tasted above 50 ppm.

He notes, however, that ratio isn’t all that matters. In subsequently perfecting his technique as head brewer at Sixpoint Brewery in Brooklyn, he settled on a chloride/sulfate ratio of 3-3.5:1 in his mash water. It’s a really powerful thing to experience.” When the NEIPA came out and everyone began exploring higher chloride to sulfate ratios, at least for me that’s when it really drove home the impact on hop expression, softness, mouthfeel and overall textural experience of IPA styles and the water chemistry impact from these two ions alone. He emails, “The traditional dogma behind IPA styles (prior to the NEIPA) was rooted in higher sulfate to chloride ratios based on historical water profiles. In fact, the BA makes only two sensory demands: 1) “hop aroma and flavor are present,” 2) “the impression of bitterness is soft and well-integrated into overall balance.”Īs brewmaster at Massachusetts’ Trillium Brewing in 2015, Eric Thomas helped pioneer the style and credits its development to a departure from the IPA water profile that informs the more traditional British and West Coast versions. The Brewers Association (BA) added them to its official style guidelines in 2018 but calls them “Juicy or Hazy” IPAs while noting that neither juiciness nor haze is required. Lawson wryly refers to his mostly clear or translucent Sunshine beers as “IPAs made in New England,” as opposed to New England IPAs (NEIPA), a term that serves as a bit of a catch-all for hoppy ales commonly typified by a soft, citrusy or tropical hop flavor a massive amount of dry hopping a gentle mouthfeel and a cloudy appearance. “If we were talking about music, sulfates might lend a staccato note whereas chloride would have more legato tones.” New England IPA Water Profile “Chloride in your water chemistry tends to accentuate the malt character and also give the mouthfeel a softer, rounder sensory experience,” says Sean Lawson, co-founder of Lawson’s Finest Liquids in Vermont, revered for its Sunshine line of balanced, juicy IPAs.

While brewers aiming for a clean, assertive hop bite to their beers do favor relatively high levels of sulfate, brewers chasing the hype of a pastry stout or today’s most popular new subcategory – the juicy IPA – prefer a higher amount of chloride in their brewing water profile. He recommends going no higher than 100ppm for this kind of beer. “It elevates the hop profile and can throw the malt balance off if the goal is to make something like an imperial stout or more malt-forward stout.” “Increased sulfate levels are not a good thing for bigger, sweeter, malt forward stouts,” says Wambles, who helped make the brewery famous for imperial stouts. For instance, the water Cigar City draws from in Tampa rotates between up to four different sources whose sulfate readings fluctuate between 70ppm and 200ppm. While a boatload of adjuncts might mask many flaws, the base of a consistent pastry stout depends first on the brewing water chemistry it consists of. Indeed, lactose-laden “pastry stouts,” as they’re often called, have so proliferated in the Sunshine State that Voodoo Brewing – headquartered in Pennsylvania – has named its version “Florida Stout.”īut brewing them in Florida can prove less sweet than the resulting liquid. Read the second article, “Water Chemistry for Brewers: Creating Classic European Beer Styles” here »Ĭigar City Brewing head brewer Wayne Wambles half-jokingly uses one word to characterize the type of stout that’s taken a strong hold in the brewery’s home state of Florida: “Underattenuated.” Read the first article, “Water Chemistry: What Every Commercial Brewer Needs to Know” here »

BEERSMITH WATER PROFILE SERIES

This is the third installment in an article series discussing water chemistry information and best practices for brewers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)